Encoding normalized floats to RGBA8 vectors

Back in the days when OpenGL ES 2.0 was the only viable way to perform efficient GPGPU computations on mobile devices, one might often need to pack and unpack a full single precision floating point value in the range \( [0;1[ \) from/to a shader’s output/input.

The following GLSL shader code does the trick

vec4 packFloatToVec4i(const float value) {

const vec4 bitSh = vec4(256.0*256.0*256.0, 256.0*256.0, 256.0, 1.0);

const vec4 bitMsk = vec4(0.0, 1.0/256.0, 1.0/256.0, 1.0/256.0);

vec4 res = fract(value * bitSh);

res -= res.xxyz * bitMsk;

return res;

}

float unpackFloatFromVec4i(const vec4 value) {

const vec4 bitSh = vec4(1.0/(256.0*256.0*256.0), 1.0/(256.0*256.0), 1.0/256.0, 1.0);

return(dot(value, bitSh));

}but the interesting part is delving into why it works.

Decomposing IEEE 754 floats in the range [0;1[

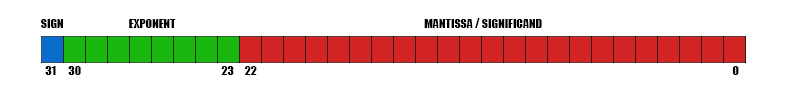

In IEEE 754 single precision floating point numbers are represented in 32 bit as follows

according to the following formula

\[\text{value} = (-1)^\text{sign}\times \left(1 + \sum_{i=1}^{23} b_{23-i} 2^{-i} \right)\times 2^{(e-127)}\]It follows that in order to store the components of a 32 bit floating point number into four 8-bit memory buffers, the number has to be decomposed first.

Let’s take the number 0.3 as an example. The floating point representation for this number is

0 01111101 00110011001100110011010

Unless the exponent is zero (depending on the significand we might have a zero or a denormal number), there is an implicit leading bit in the significand, therefore the number can be expressed as

\[\begin{align} s & = -1^0 = 1 \\ e & = 125 - 127 = -2 \\ m & = 2^{-2} + 2^{-5} + 2^{-6} + 2^{-9} + 2^{-10} + 2^{-13} + 2^{-14} + 2^{-17} + 2^{-18} + 2^{-21} + 2^{-22} + 2^{-25} + \\ & 2^{-26} + 2^{-29} + 2^{-30} + 2^{-33} + 2^{-34} + 2^{-37} + 2^{-38} + 2^{-41} + 2^{-42} + 2^{-45} + 2^{-46} + 2^{-49} + \\ & 2^{-50} + 2^{-53} + 2^{-54} \end{align}\]notice that the mantissa values are dependent on the exponent itself.

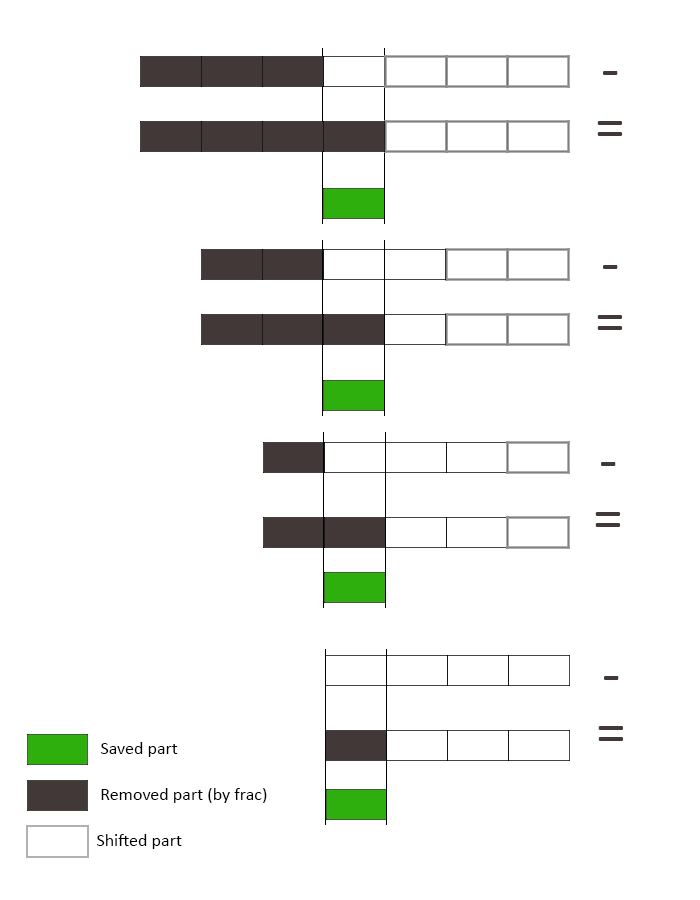

Now if we multiply this number by 256, it will be like adding 8 (\( 2^8 \)) to the exponent and therefore preserving the mantissa but shifting the exponent by 8 bits. This will, in turn, change the value of the negative powers of all components of the mantissa

\[\begin{align} s & = -1^0 = 1 \\ e & = 133 - 127 = 6 \\ m & = 2^{6} + 2^{3} + 2^{2} + 2^{-1} + 2^{-2} + 2^{-5} + 2^{-6} + 2^{-9} + 2^{-10} + 2^{-13} + 2^{-14} + 2^{-17} + 2^{-18} + \\ & 2^{-21} + 2^{-22} + 2^{-25} + 2^{-26} + 2^{-29} + 2^{-30} + 2^{-33} + 2^{-34} + 2^{-37} + 2^{-38} + 2^{-41} + 2^{-42} + \\ & 2^{-45} + 2^{-46} \end{align}\]notice that some components have become positive: the number is no longer in the range \( [0;1[ \). If we were to save these positive components we could get the fractional part of this new number, dividing it by 256 (in order to shift it back in the original position) and subtract this quantity from the original number.

And that is exactly what the packFloatTOVec4i() routine is doing. Simplifying the code for a single 8-bit component one could write

const float bitSh = vec4(256.0*256.0*256.0, 256.0*256.0, 256.0, 1.0);

const vec4 bitMsk = vec4(0.0, 1.0/256.0, 1.0/256.0, 1.0/256.0);

float reduced_fractional_part = fract(value * 256.0) * (1.0/256.0);

first_part = original_number - reduced_fractional_part;A graphical representation of the operations involved and of the packing performed by the packFloatTOVec4i() routine into the vec4 parts

follows

E.g. suppose that a part of the above decomposition was \( 0.625 \). This value corresponds to \( 0.625 \cdot 256 = 160\) when encoded as an

unsigned byte in the range \( [0;255] \). In binary \( 160 \) is 10100000 and this amount will be stored in one of the 8-bit buffers.

The exponent is therefore implicitly deduced.

Furthermore it might be worth repeating that the above considerations and the code snippets only work for floating point values in the range \( [0;1[ \).

Credits

-

The packing/unpacking routines were found on various websites and probably originated from gamedev.net, in no way I claim ownership on these snippets.

-

A huge thank you to Gernot Ziegler for reviewing and helping me out with this post.

-

Thanks to Bryan Wagner for pointing out a range error.